0.0000% of a Kilogirl.

This percentage combines your current time on the page with the total time spent by all previous visitors, out of a target of 1000 hours.

When the site reaches a Kilogirl, the count will reload.

A ‘kilogirl’ is a material unit that for a short time in the mid-twentieth century measured computer power, based on the women whose work underpinned the computers’ operations. A ‘kilogirl’ represents the computer power of 1,000 women doing one hours’ worth of work. The collective Superkilogirls researches the material infrastructures of computing, its entanglement with women’s labour, and how the historical marginalisation of these efforts reverberates now.

This website launches the first few research projects by Superkilogirls in several chapters:

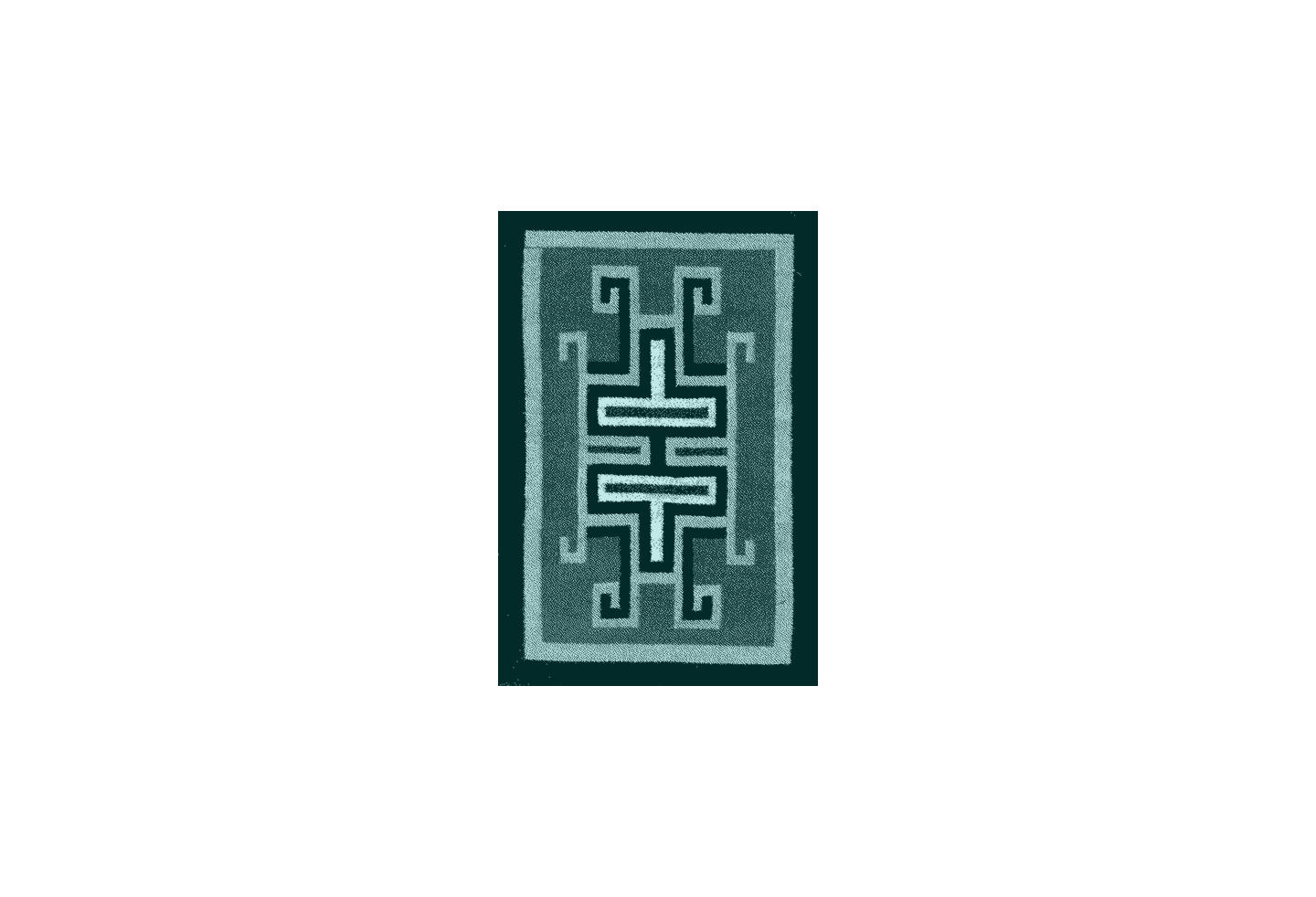

- Kilo Weavers → on the contemporary relevance of the Luddites

- Heirs of All Knowledge → on Bell Labs' feminised employment guide

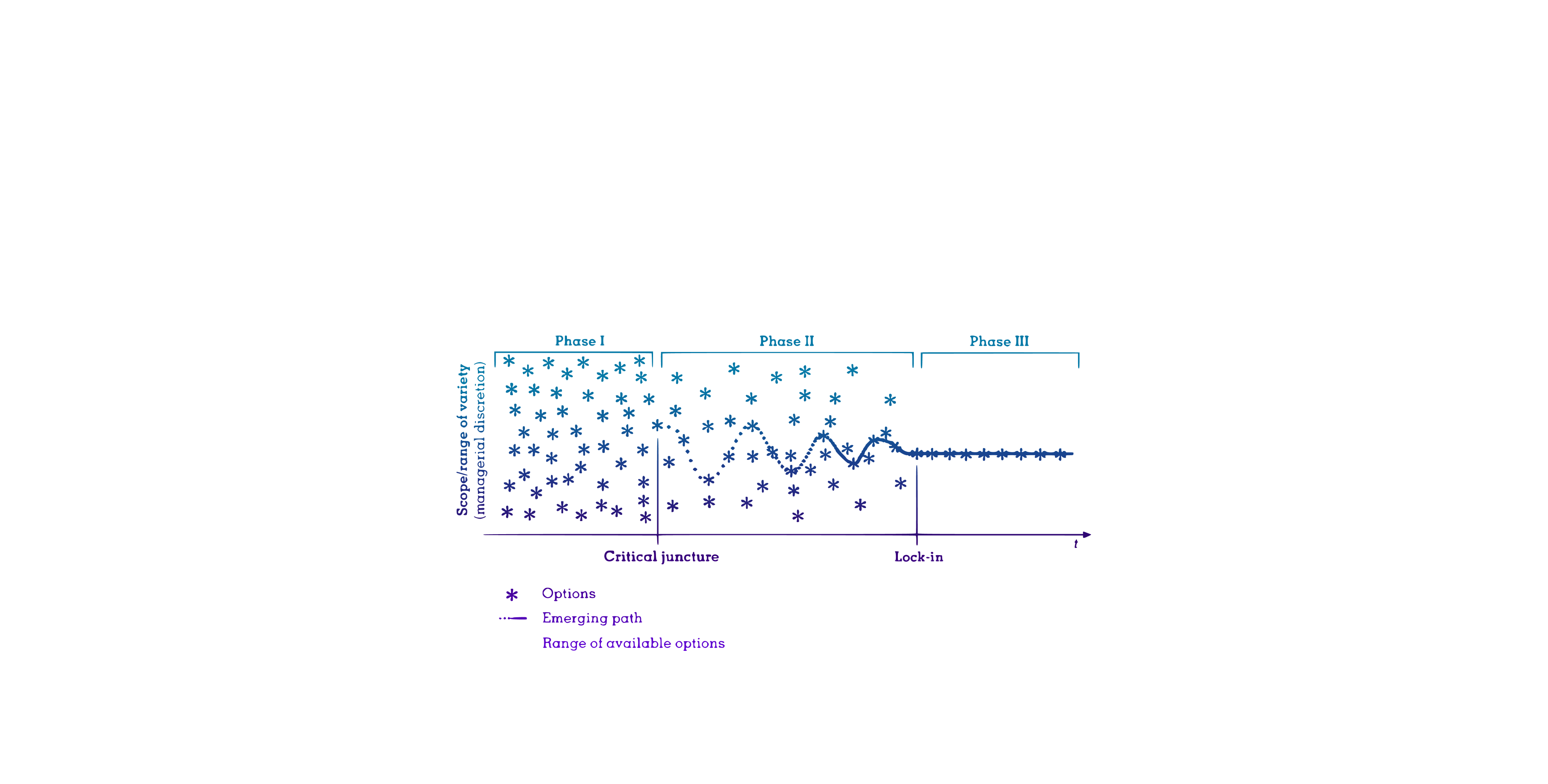

- Locked In → on the technological determinism of ASML

- Real Girls' Work → on the women workforces at Phillips Semiconductors

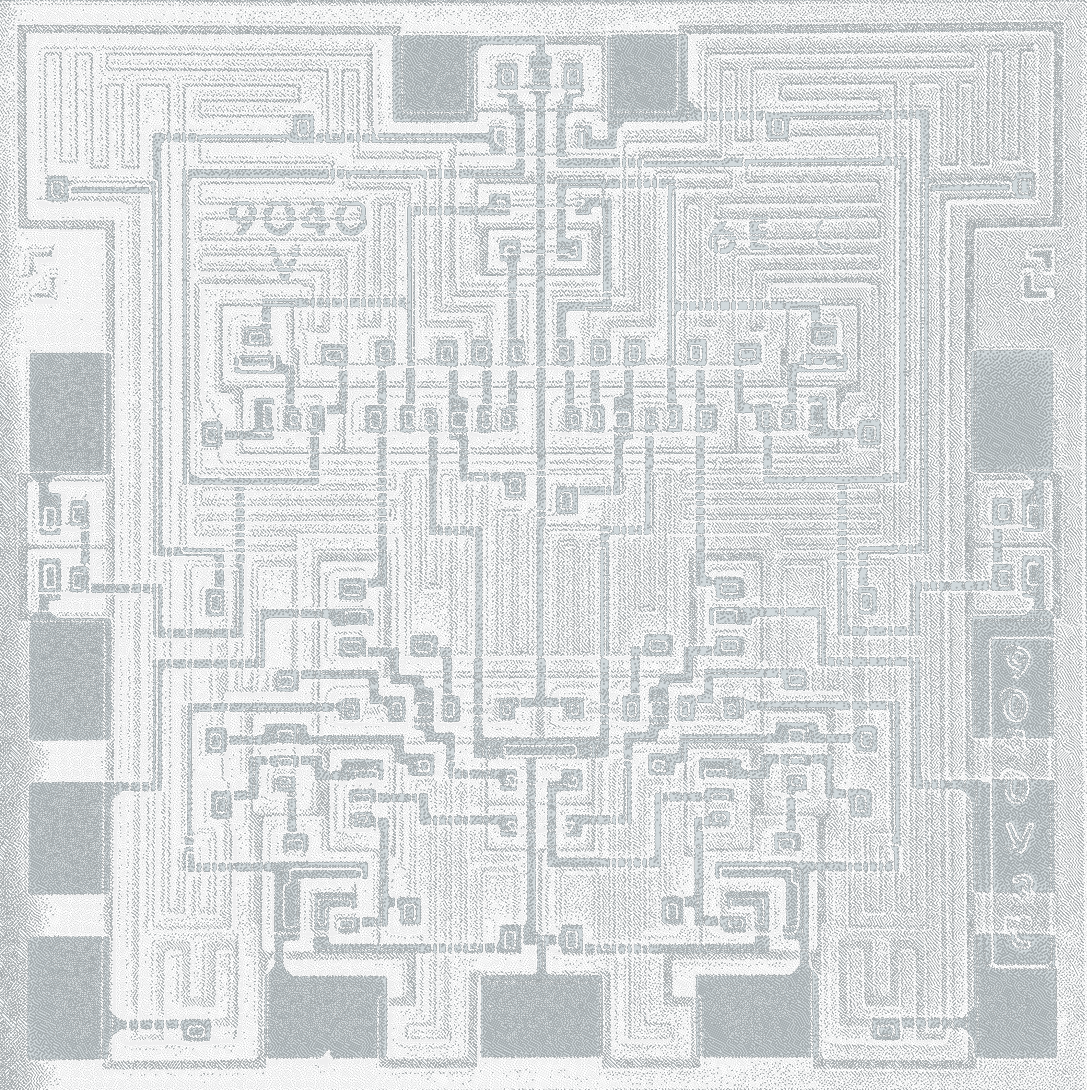

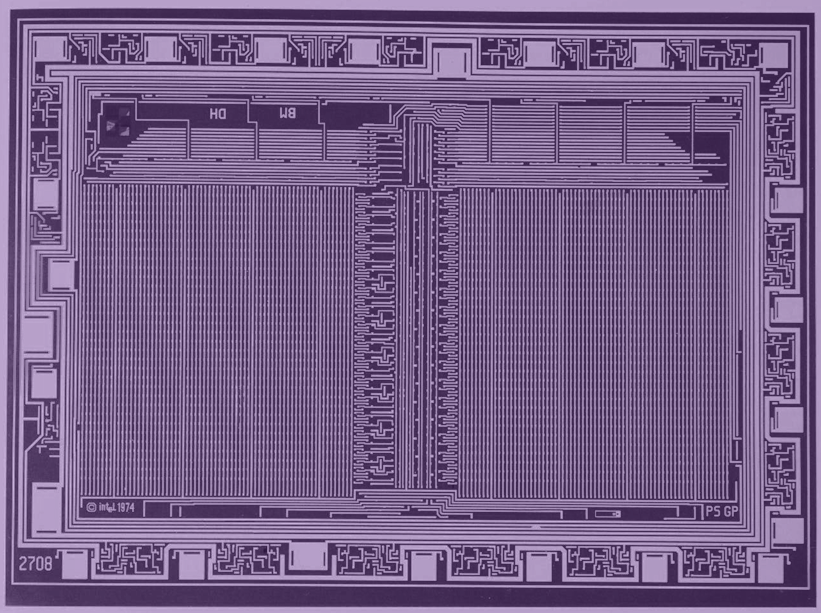

- Machine, Information, Art → on microchip diagrams at MoMA

- The Manual for Superfluous Motions → on performing semiconductor production

Based on site visits to Hudderfield and Skelmanthorpe, Kilo Weavers recounts the Luddites' fight against mechanised labor that threatened traditional crafts and workers' autonomy, and traces the contemporary recurrence of machines replacing the workers that wield them.

Ana Meisel

Heirs of All Knowledge contends with the historical role of female switchboard operators at Bell Telephone Company from the 1910s to the 1940s, examining the autonomy of their labour in the context of rapidly advancing technological systems.

Camila Galaz

ASML manufactures some 90% of the world's machines that produce microchips. Locked In investigates how Moore's Law has driven the technological determinism that has expanded ASML's monopoly by exponentially shrinking transistors over the past 30 years.

Lua Vollaard

An ascending workforce of girls is employed by Philips Semiconductors. Real Girls' Work traces how global high-tech employment in microchip manufacturing has historically become a container for a particular type of girlhood.

Lua Vollaard

In 1990, MoMA exhibited microchip diagrams in the historical exhibition Information Art. The text recounts its museological ancestors, Machine Art and Information, while contextualising the curators' effort of locating the diagrams between functional design and artistic object.

Lua Vollaard

Superkilogirls is a project by Lua Vollaard, Ana Meisel, and Camila Galaz

The project has been presented at:

Framer Framed, Amsterdam

Het Nieuwe Instituut, Rotterdam

Triple Canopy, New York City

New Inc., New York City

Permacomputing Club, London