Real Girls' Work

August 7, 2024

From 1953 to 2006, Philips operated a semiconductor factory in Nijmegen, a town some 75 kilometers from their base of operations in Eindhoven. Over the course of the previous century, Philips had made great strides in the expansion of their factory there, attracting workers first from the area, then from rural areas further out in the Netherlands, finally recruiting from other countries altogether. As a prototypical company town, Philips provided housing, stores to buy their products, and extracurricular community activities. Workers from different places were housed together, in neighbourhoods that took their name from their main inhabitants, such as the Drentse Dorp. Eindhoven was soon running out of workers; expansion was on the horizon. Emmen was considered for a new factory, but Nijmegen was ultimately selected. Its relative proximity, historical cultural center, and upscale residential accommodation for senior executives got it past the finishing line.

’50 Jaar (H)erkennen’ (Acknowledging / Recognizing 50 Years) is the title of the corporate history of Philips Semiconductors Nijmegen, published on behalf of their ‘golden’ anniversary in 2003. One of the very first photos in their historical retelling of the factory is that of a travelers’ camp. Black cars are parked for inspection of the lot, which houses wooden trailers, carts, and clogs, with a few children in rags visible in the background. A caption in the book tells us that the trailer park ‘made way’ for Philips Nijmegen. Technology drives gentrification even before its production lines have started up.

Semiconductors were first developed in the United States company Bell Labs in 1947. Technological inventions moved quickly; by September 1951, Bell organised a conference to share their findings with 300 scientists from all over the world. Philips was an industry leader in electron tubes back in Europe, and anticipated the annihilation their market share by the much smaller component. Since 1950, the Philips Nat.Lab joined forces with Bell Labs through a collaborative contract. Instead of waiting for the competition in Europe to catch up, Philips essentially decided to compete with itself in their Nijmegen factory. The race was off.

For fifty years, Philips Semiconductor Factory operated out of Nijmegen, making microchips for household appliances, and chalking up a few internationally important patents. Colour television was invented here; coffee makers and shaving apparatuses alike turned smart. After such lucrative years, the factory was eventually taken over by the US giant NXP in 2006. The issue of recruitment persists even now – the factory had their own recruitment office from the very start, and the recruitment agency Randstad still operates out of the NXP factory. The archives of Philips Semiconductors were found in a shed on those factory premises, and were moved by LINK foundation in collaboration with a number of pensioned factory workers. They are now situated in an active rubber factory elsewhere in Nijmegen. Housed in an upstairs room, and tended to every Monday by a handful of volunteers who are mostly pensioners of the factory, the archives encompass two unsorted treasure rooms of chip drawings, silicon wafers at various stages of the production process, and file cabinets full of printed images. Many photobooks show working conditions at the factory, groups of women being served coffee, walks along the lake, a gaggle of women in white lab coats leaving the factory. Documentation of office parties is shuffled with images made for recruitment and training purposes. A scrapbook features newspapers cutouts about the factory.

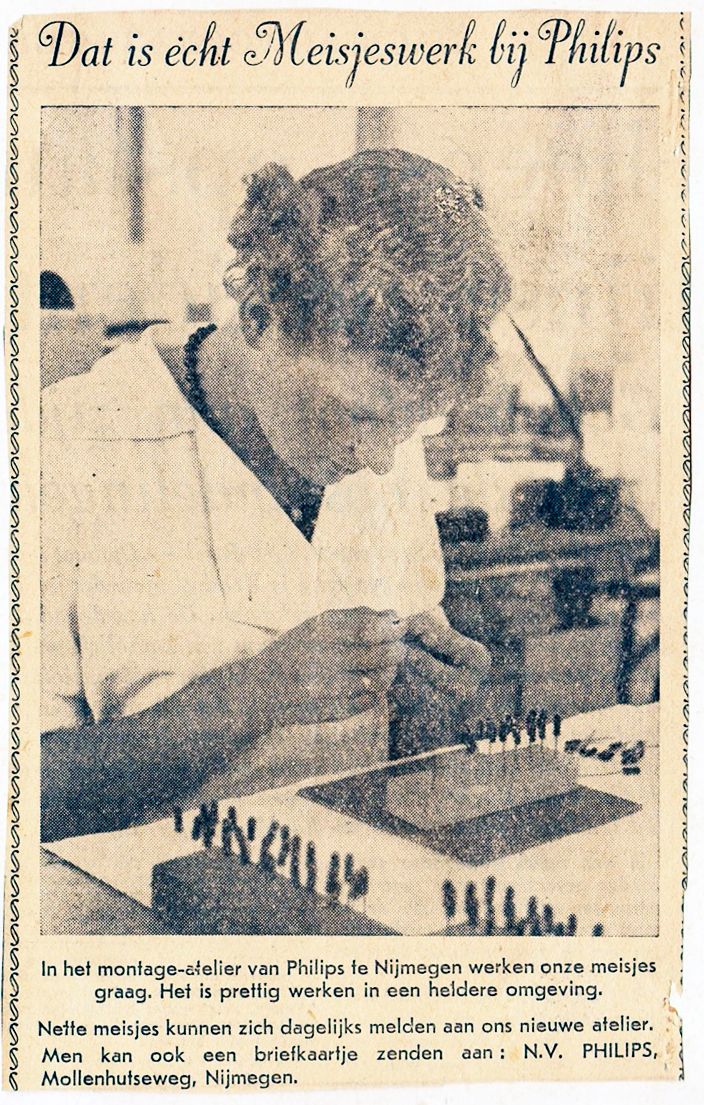

Having entered the workforce during the second world war, by the 1950s it was admissible for middle class women, albeit unmarried, to keep a job. Throughout the mid-fifties, Philips placed advertisements to recruit women; most of them show groups of smiling women in white lab coats on meticulously maintained company grounds. Cursive typology informs readers of conditions in the factory, such as the cantina. One of the main adverts, run in the provincial newspaper De Gelderlander, advertises Real Girls Work – echt meisjeswerk. Small print in nearly each one of the adverts specifies them to look for ‘nette meisjes’ – neat girls.

In Dutch, ‘echt meisjeswerk’ loses the double meaning ‘real girls work’ has in English. It merely refers to the type of work as suitable for girls; the English verb also denotes the possibility of working as underwriting an identity – manufacturing will turn you into a real girl. The category of 'girl' here becomes a category of a waged labourer. It both includes and excludes. To be a woman is to be a homemaker, and so the nascent category of woman workers is only open to 'girls'. Philips had a vested interest in its underwriting of feminine identity within their search for cheap labour. A letter sent in to the newspaper is collated in the scrapbook; it complains that the women who are being lured with promises of clean work are being taken away from homemaking and childcare duties. Local anxieties around the loss of women in the home drive Philips to a strategy that was primarily affirming of labourers’ gender identity. ‘Neat Girls’, additionally, is a not so subtle call to girls of a certain racial and class standing. It’s hard to image that girls from the displaced travellers’ camp would’ve been welcome to jobs at the factory.

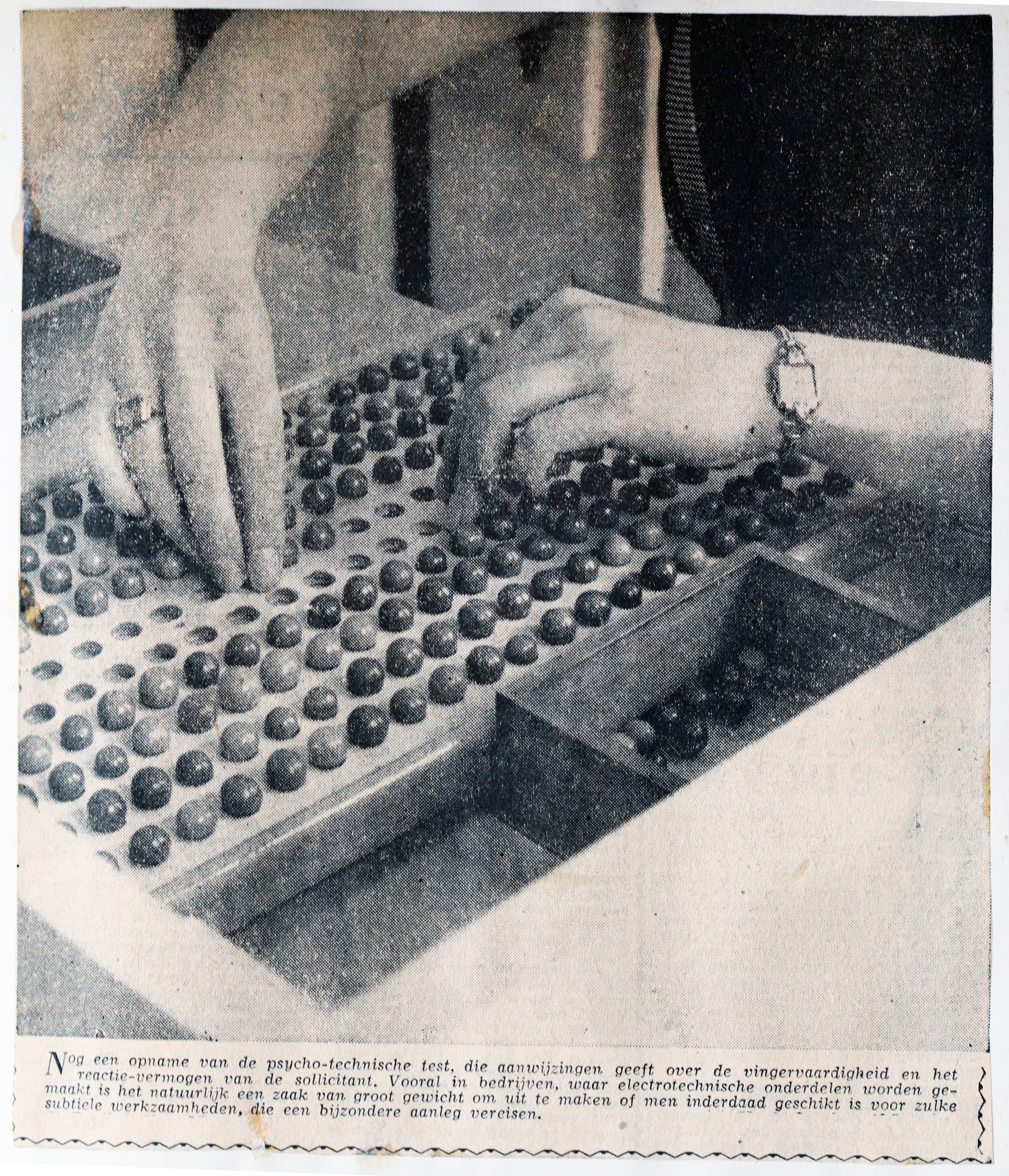

The adverts showed the workplaces that girls would be taking up. They are advertised as clean, bright work spaces, and use the word ‘studio’ (atelier) as opposed to the heavy-industry associations of ‘factory’. Crucially, the work places shown were individual stations, and so not as part of an assembly line, allowing girls to ‘decide on their own tempo’. One advert shows a ‘psycho-technical test’ administered as part of the application procedure that tests dexterity; a woman’s hands, meticulously manicured and embellished with metal jewelry, selects different coloured balls from a small wooden board. All these materials are meticulously presented to present microchips assembly much like the handwork that many women are already fulfilling at home.

In On Software, or the Persistence of Visual Knowledge, Wendy Chun writes about the programming of the first computers, a task almost entirely performed by women whose job titles would later lend the machines their name. The essay traces the development of programming as a professional subfield, arguing that women were cast out from the field just as it started to form: “programming became programming and software became software when commands shifted from commanding a “girl” to commanding a machine.”[1] Software takes its name from the first computer, the Jacquard loom, which automated weaving. The loom used punch cards to allow intricate patterns to be woven by directing the levers that held the threads of the loom in place. The machine "effectively withdrew control of the weaving process from human workers and transferred it to the hardware of the machine",[2] originating the differentiation between the hard ware of the machines that automated human labour, and the soft wares that they produced. At the genesis of programming on mainframe computers, this work had an equal workforce of men and women because it is not yet a profession. ‘Women’, Chun writes, ‘have been largely displaced from programmers to users, while continuing to dominate the hardware production labor pool even as these jobs have moved across the Pacific.’ While the implementation of Jacquard machines was ‘bitterly opposed by workers who saw in this migration of control a piece of their bodies literally being transferred to the machine’[3], a hundred years later, in Nijmegen, machines again provided a temporary form of emancipation before replacing the workers whom tended to them. Wages allowed the women in the semiconductor workforce to leave the home, replicating the same intricate handwork they were performing there. Before the end of the 1970s, most of the jobs of the women working at the factory has been outsourced to the Global South; the repeated gestures of their fabrication, the muscle memory involved with the microscopic scale of their production, disappeared into the black box of household appliances that soon themselves obsoleted.

There is a longer history in which technology companies harbour the fine skills of women handcrafters, only to replace those workers with outsourced labour to even cheaper places before automating their labour entirely. A paper by Lisa Namakura details the venture of Fairchild Semiconductors, a frontrunner to Intel, outsourcing the work of semiconductor fabrication to Navajo women. The reservation, which Fairchild leased from the Navajo nation, provided an exception to US minimum wage standards. A 1969 dedication brochure for Fairchild Semiconductor’s new Shiprock facility, on Navajo lands, shows the likeness of their semiconductors to Navajo woven fabrics. The cover page of the brochure simply shows a Navajo blanket, with no title or caption. A full bleed photo inside shows one of the products of the Shiprock facility, a Fairchild 9040 integrated circuit,used in communications satellites like COMSAT. The pairing of the two images in the booklet strongly suggests the analogousness of the weaving with the microchips. The original captions read:

The Talents of the Navajo people reach beyond imagination. A Navajo woman weaves a perfectly patterned rug without seeing the whole design until the rug is completed. Weaving, like all Navajo arts, is done with unique imagination and craftsmanship, and has been done that way for centuries... Building electronic devices, transistors, and integrated circuits, also requires this same personal commitment to perfection.

The unexplained likeness of the two images suggests that Navajo weaving is “merely a different material iteration of the same pattern or aesthetic tradition found within the integrated circuit”.[4]The text of the booklet heavily trades in ideas of indigenous Americans as craft workers, producing circuitry as a ‘labour of love’ for the craft rather than for a wage. These high-tech handcrafts, argues Nakamura, ‘produced a complicated identity’ that positioned ‘position the Navajo on the cutting edge of a technological moment precisely because of their possession of a racialized set of creative cultural skills in traditional, premodern artisanal handwork.’ In the end, Fairchild’s foray into the Navajo nation leads to outsourcing; by then known as Intel, the company moves its production lines to Mexico, Singapore, and Hong Kong, then contracting a Taiwan foundry which automates the process entirely.

The story of Shiprock has recently been circulating in the art world through the incredible work of Marilou Schultz, a fourth-generation Navajo weaver. Commissioned by intel in 1994 to weave a replica of the Pentium Microprocessor, Intel used an image of Schultz work alongside a faithful reproduction of the chip in their publicity, stressing the likeness of Navajo arts to high-tech production as late as the 1990s.

Semiconductor manufacturing, before it automation in the mid-80s, was painstaking work. It requires a microscope, excellent eyesight, and an exhaustive dexterity. The gestures that have been embedded into our devices encapsulate a history of handwork. Hardware production, from its inception with the Jacquard loom to the handwork of semiconductor manufacturing from Nijmegen to the global South, has produced a container for female identities along with it, one that started from- and reaffirmed the worker's 'girlhood' as a precondition for labour. The choreography of semiconductor manufacturing, with its repeating, personalized gestures, has scored technological development in both senses of the word – a score to provide a template, and a score to provide a mark. Those traces are good to bear in mind when we arrive to the entagnled, machinic notions of woman proposed by Donna Haraway’s pioneering Cyborg Manifesto, of which the subtitle reads: “An Ironic Dream of a Common Language for Women in the Integrated Circuit”.

[1] Wendy Chun, On Software, or the Persistence of Visual Knowledge, p. 33

[2] Manuel de Landa, War in the Age of Intelligent Machines, p. 168.

[3] ibid

[4] Lisa Nakamura, Indigenous Circuits, 2014.