Kilo Weavers

December 29, 2024

“In the factory, we have a lifeless mechanism independent of the workman, who becomes its mere living appendage.”

– Marx, Karl, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy. Vol. 1, Chapter 15.

During the 17th century, much of Europe witnessed widespread uprisings by workers against the ribbon loom, a mechanised device used for weaving ribbons and decorative trimmings that threatened traditional handweaving crafts at the time. Artisans saw it as a direct challenge to their livelihoods and economic security and it eventually became prohibited by authorities across Europe between 1629 and 1719 and even faced public destruction[1]. The prevalent opposition to looms was a political threat as much as a populist one, generating powerful combativeness from workers. Cloth work of spinning and carding which was historically carried out by women was the first to be mechanised. In England, James Hargreaves initially kept the secret of a machine that automates the spinning of yarn. But in 1766, food riots and falling wages angered spinners, and they destroyed his spinning jennies, forcing him to flee.

Britain relied heavily on raw cotton throughout the post-medieval period, "the most important raw material of British industry"[2]. It was primarily sourced from inside the Empire, particularly India, which was the world's leading producer of cotton textiles under British colonial rule. Reflecting on the devastating impact of this exploitation, Lord William Bentinck, a former Governor-General of India, wrote in 1834: “The misery hardly finds a parallel in the history of commerce. The bones of the cotton weavers are bleaching the plains of India.” As Britain's textile industry relied on the exploitation of India’s resources and labour, its colonisation foreshadowed modern outsourcing practices, including the transfer of large-scale data processing for artificial intelligence to India, where lower costs continue to drive such operations.[3]

The Industrial Revolution intensified this Early Modern hardship as the power loom rendered skilled handweavers obsolete. The resulting unemployment, starvation, and social unrest led to the Luddite movement, where textile workers organised machine-breaking riots against factories and machinery they blamed for their struggle. The government responded with military force and harsh penalties and ultimately enforced the Frame Acts and suppressing the movement by the 1820s.

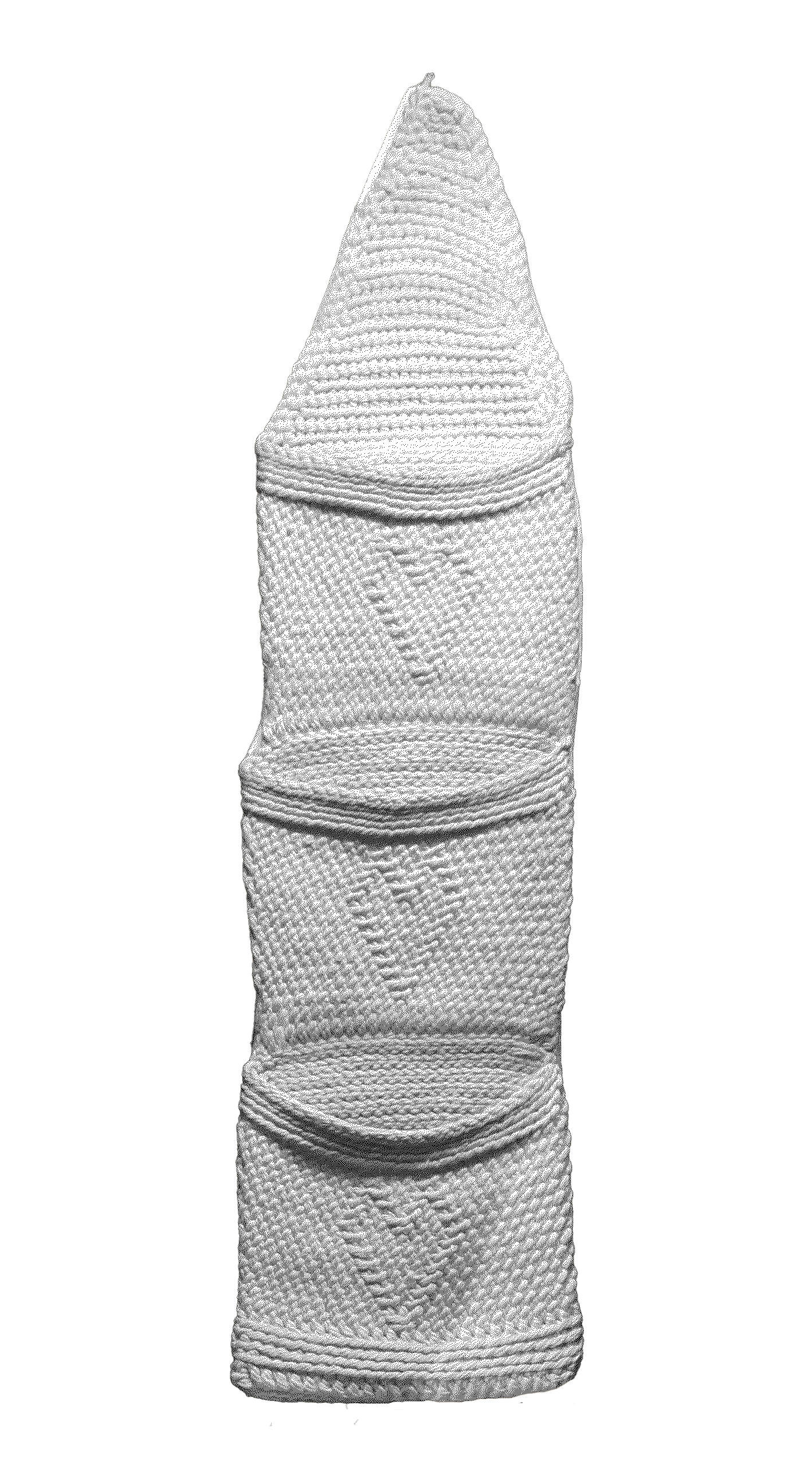

Huddersfield, once a hub of Luddite activity, was home to numerous mills that housed the workers central to the movement. Albion Mills, Aspley Mills, Bay Hall Mills, and Britannia Mill have all disappeared, leaving no evidence of their history or former presence. The town is home to Alan Brooke, a leading Luddite historian, and the Tolson Museum in Ravensknowle Hall, which showcases Luddite memorabilia. A standout piece is a hair tidy crafted by a renowned Luddite from Huddersfield, William Thorpe. Thorpe created this intricately crocheted piece, adorned with sewn-in hearts, while imprisoned in York Castle in 1813, awaiting trial for the murder of mill owner William Horsfall. Thorpe was hanged and dissected alongside George Mellor and Thomas Smith on January 8th of that year. As he created the hair tidy within the confines of his cell, it lives on as a reflection of the repetitive, dehumanising labour that had become second nature. Thorpe’s muscle memory turned to creation, crafting a functional object as an act of quiet defiance. This small gesture of care amidst chaos disclosed a life shaped by relentless toil and ended violently in his resistance to industrial oppression. Knitting and embroidery, common pastimes for prisoners, become here a materialisation of time, waiting, and resistance.

The Luddites’ organised militancy and direct action against industrial machinery are an important symbol of resistance as well as an immediate response to workers’ material conditions. Karl Marx captured this as such: “Since the introduction of machinery has the workman fought against the instrument of labour itself, the material embodiment of capital.” Initially, the indiscriminate machine-breaking riots targeted all machinery within workhouses. But over time, the Luddites began strategically aiming at machines in factories owned by particularly obstinate mill owners (and, in cases like Thorpe's, the mill owners themselves). It marked the first instance of class consciousness in Britain, shaped by the introduction of industrial machinery.

Machines can oppress, driving ordnance, dependency, labour displacement, environmental harm, biodiversity loss, and extinction. By exposing this "dead labour," they raise a critical question: does their introduction highlight societal divides by serving as tangible symbols of inequality? The Luddite movement illustrates these dynamics, linking opposition to machinery with broader social tensions and conflicts.

Among the Luddites were ex-soldiers from the Napoleonic Wars. They were skilled in organising and executing coordinated actions. The Luddites operated as a secret society, recruiting members through clandestine oaths despite the fact that oath-taking was punishable by death. They carried out nighttime raids to smash industrial machines, armed with hammers crafted by Enoch and James Taylor which was same company that produced the very machinery they opposed. Disguised in women’s clothing to conceal their identities, they were celebrated as subversive working-class heroes of their time. This form of "camouflage drag" can be seen as a symbolic intersection between traditional roles of men and women. Historically invisible reproductive labour, such as care work, is now a major employment sector in the UK and US, spanning healthcare, education, food service, and insurance.[4] Yet, these roles are increasingly automated or outsourced. This occurrence is sustained by the “feminisation” of the proletariat with many factory jobs continuing to be filled by migrant workers.[5] Like housework before it, this hidden world of production remains largely ignored. This "Jet Age Automation"[6] perpetuates the invisibility of certain labour.

In contrast, the Luddites wanted to be as politically conspicuous as possible. They sent threatening letters, signed under the alias “King Ludd” or “General Ludd,” and warned factory owners to dismantle their machinery or face destruction. Along with groups like the Jacobins and the Chartists, they posed one of the greatest internal threats to the English government. Their intimidating uprising prompted the government to devise new methods of suppression, and Robert Peel’s establishment of the Metropolitan Police was partly aimed at quelling such populist revolts.[7]

The Luddites’ actions were a desperate attempt to resist the encroaching horrors of industrial capitalism and to preserve a way of life that was rapidly disappearing. While they opposed labour-replacing technologies that stripped them of their agency, they aimed to protect tools like handlooms which enabled more freedom and skill. The Luddites were not anti-technology; they were defenders of a balance between labour and tools that upheld the autonomy of the worker. The movement persisted throughout the Industrial Revolution, almost as if it were driven by a sense that life would never be the same again. Or by intuition that these macroinventions[8] would trigger a snowball effect, with textile machines continuously fueling further technological advancements. One of the machines they were breaking was the Jacquard loom, a device that laid the groundwork for modern binary technology. Its punch card system encoded patterns as holes or no holes which later inspired Charles Babbage's Analytical Engine and the foundations of computer programming and digital logic.

In small family weaver’s cottages, such as the one at the Skelmanthorpe Textile Heritage Centre near Huddersfield, the loom typically dominated the upper floor. These cottages were common among weaving families, designed to accommodate the handloom as the centrepiece of the household. Its massive presence shaped the structure and function of the home, often leaving children with no choice but to sleep in or around the loom. It was an integral part of the home’s architecture and daily life. Routines revolved around relentless labour with weavers working more than 12 hours a day in this confined and demanding environment. The woven cloths were typically sold directly from the doorstep to merchants, reinforcing the home’s dual role as both living space and workplace. The upper floor ceilings were designed to be high enough to accommodate the loom with long rows of windows strategically placed to maximise natural light. A "taking-in” door, often now sealed, allowed wool to be brought into the loomshop and finished cloth to be removed.[9]

These purpose-built centres of production and lodging supported a mercantilist structure of family labour. Work was seasonal, involved the entire household, and allowed weavers to operate as skilled freelancers, maintaining control over their labour. Industrialisation fractured household production and a type of family unity as factory machines and Taylorist systems alienated and enraged workers. This gave rise to a collective resistance and solidarity that the dispersed domestic industry could not achieve. It was only when they were thrown into the “dark Satanic Mills” (William Blake, And Did Those Feet in Ancient Time, 1808), that a new form of solidarity began to emerge.

As Brian Merchant explains in Blood in the Machine (2023), “In the 1800s, automation was not seen as inevitable, or even morally ambiguous. Working people felt it was wrong to use machines to ‘take another man’s bread.’” The Luddites' struggle was against the soulless machinery that reduced workers to mere extensions of capital. The term "Kilogirl" aptly captures this – a tongue-in-cheek measure of computational power that replaced human labour. It serves as reflection of technology's role in eternalising the cycle of production and profit. These transitions highlight a recurring pattern: the tools of progress often displace the very workers who first wielded them. If innovation begs for a human cost, then what does progress mean?

First image: William Thorpe's hair tidy, crocheted right before his execution on the 8th of January 1813. Courtesy of the Tolson Museum in Huddersfield, West Yorkshire, England.

Second image: Photo by Fred Hartley, date unknown. Courtesy of the Tolson Museum in Huddersfield, West Yorkshire, England.

Footnotes

1. Mehring, F. (1893). On historical materialism. Retrieved from https://www.marxists.org/archive/mehring/1893/histmat/

2. Robbins, L. (1937). Economic planning and international order (p. 247). London: Macmillan.

3. CBS News. (2023). Labelers training AI say they’re overworked, underpaid, and exploited. Retrieved from https://www.cbsnews.com/news/labelers-training-ai-say-theyre-overworked-underpaid-and-exploited-60-minutes-transcript/

4. Fraser, N., & Jaeggi, R. (2024). Capitalism’s crisis of care: An exchange. Past & Present. Advance online publication

5. Birketts LLP. (2023, July 19). Women migrant workers. Retrieved from https://www.birketts.co.uk

6. Selinger , E., Sadowski, J. The Tools of Their Tools. Retrieved from https://www.thenewatlantis.com/publications/the-tools-of-their-tools

7. Lyman, J. L. (1964). The Metropolitan Police Act of 1829. Journal of Criminal Law, Criminology & Police Science, 55(1), 141. Retrieved from https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=5222&context=jclc

8. Crafts, N. F. R. (1995). Macroinventions, economic growth, and the 'Industrial Revolution' in Britain and France. The Economic History Review, 48(3), 443–461. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/2598183

9. MyLearning. (n.d.). Domestic woollen industry and weaving in the Colne Valley. Retrieved from https://www.mylearning.org/stories/domestic-woollen-industry-and-weaving-in-the-colne-valley/1077