MoMa’s Information Art, 1990

February 18, 2025

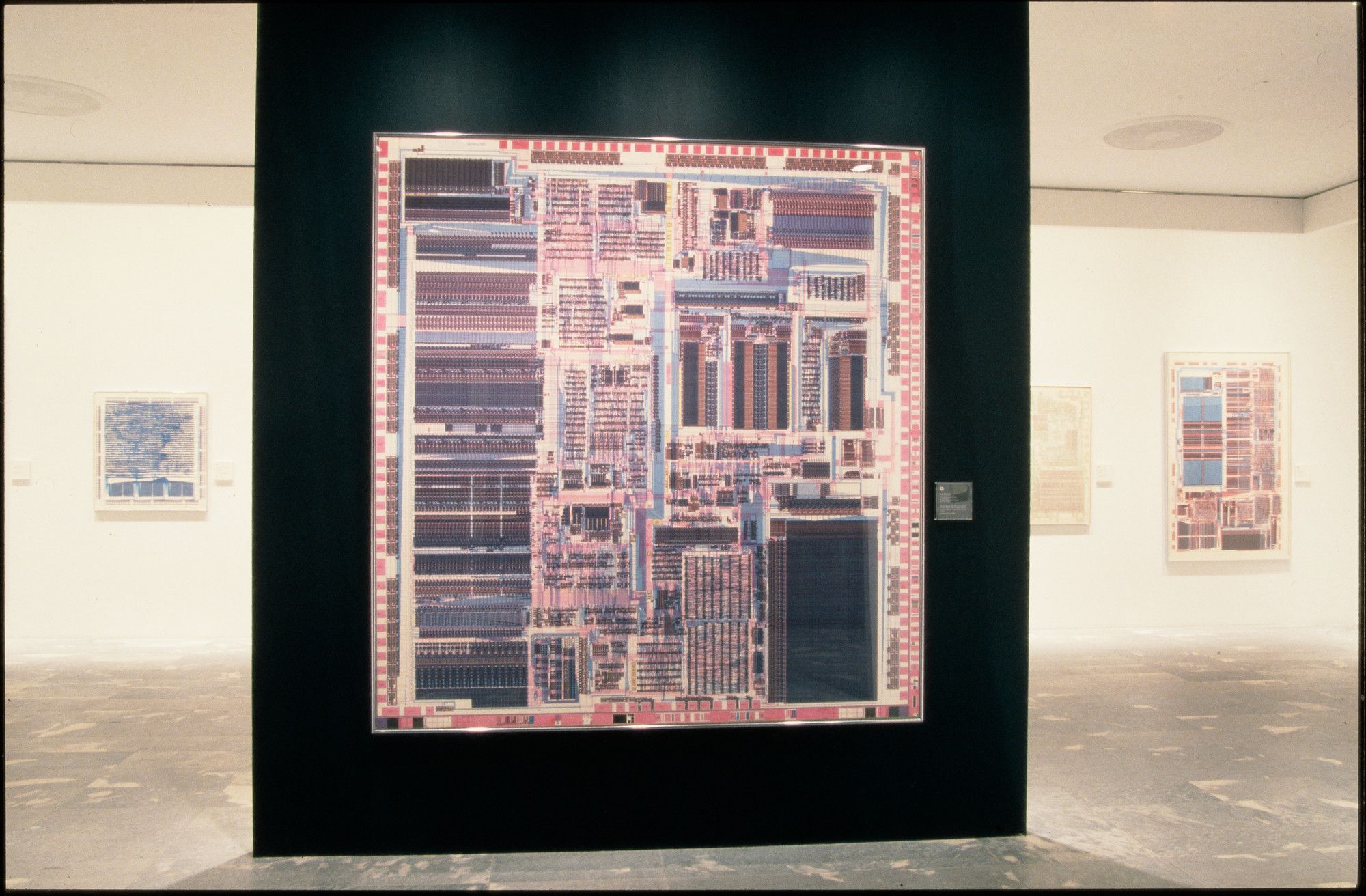

In 1990, a small exhibition at MoMA brought together a number of microchip diagrams. Curated by Cara McCarty, Information Art: Diagramming Microchips was made possible by the Intel Corporation Foundation and featured 29 diagrams by the likes of Texas Instruments, IBM, Intel, AT&T Bell Laboratories, Hewlett-Packard, Xerox, and more. Carver Mead and Robert Noyce, both inventors of the technology, were advisors on the show. Noyce was the first to conclude that integrated circuits could be placed on a single, microscopic chip. He co-founded Intel and Fairchild Semiconductors. He passed away before the exhibition opened; the catalogue is dedicated to him. On display at MoMa, by then, is a foray into the artworld to his legacy as the ‘Mayor of Silicon Valley’.

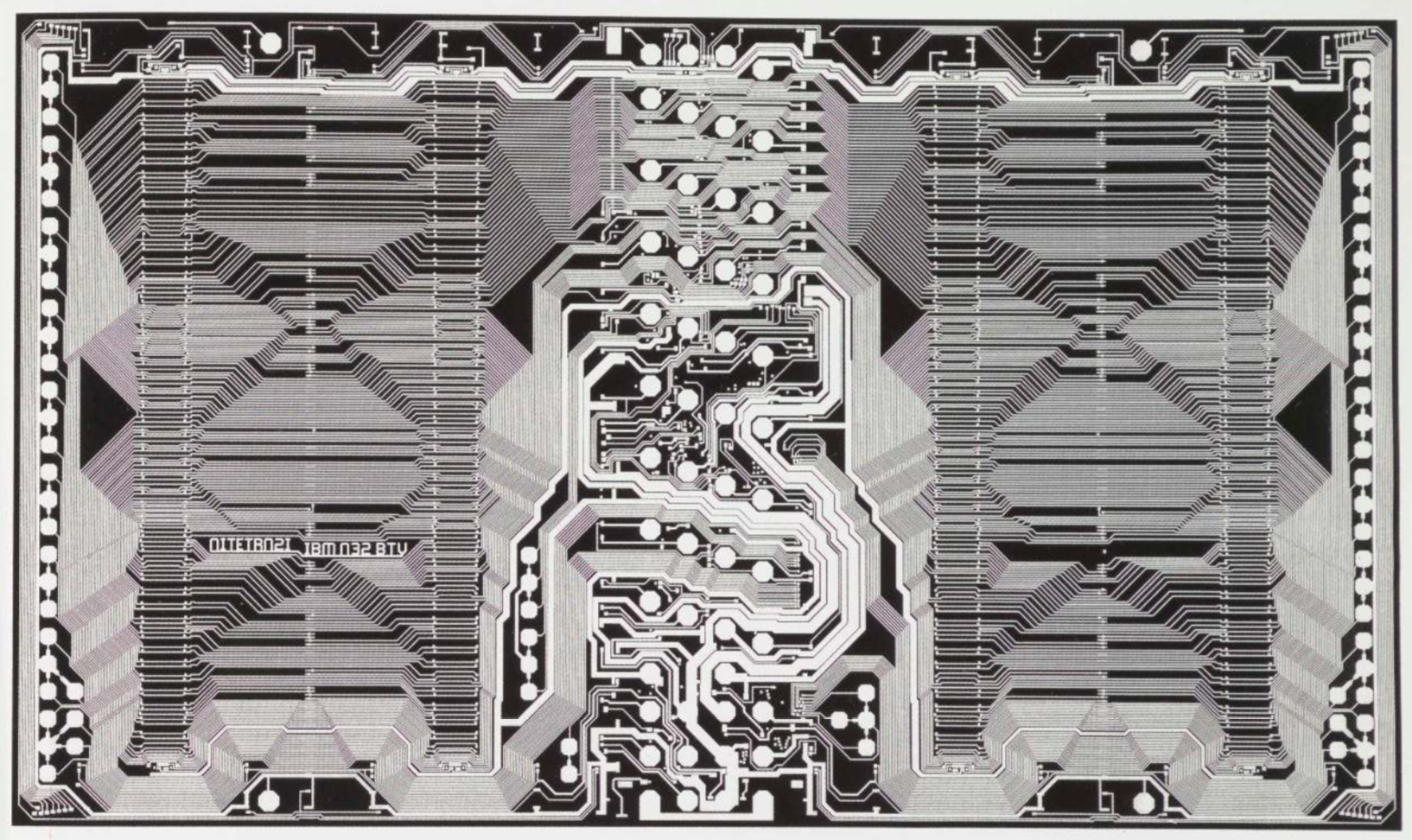

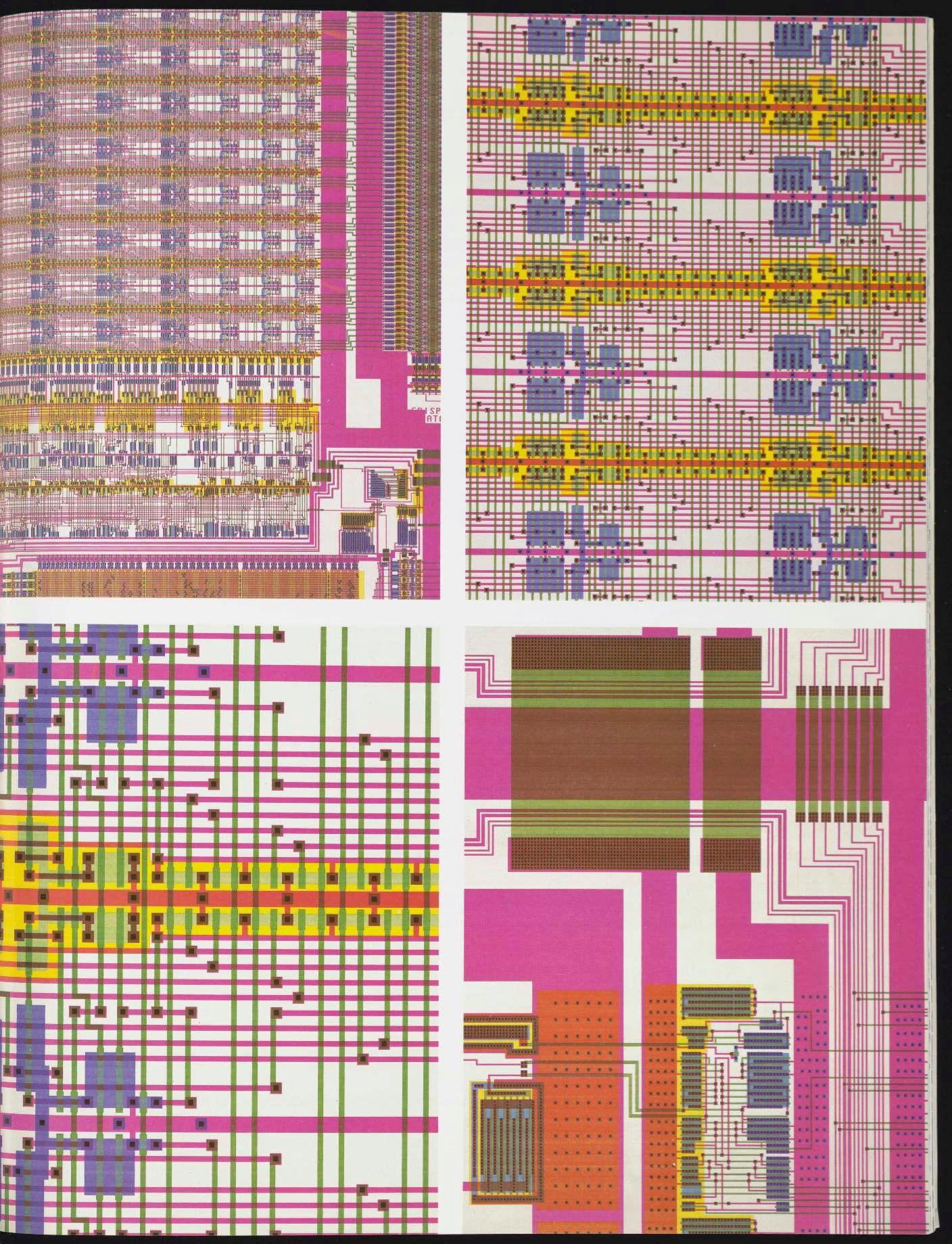

The catalogue is didactic, going to great lengths to explain the history and importance of microchips in layman’s terms. It also emphasises the craft elements to the production processes. Microchip diagrams are, still today, the templates from which microchips are produced. At the time of the exhibition in 1990, these diagrams were the product of a manual process, its design process not yes completely digitized, its production process not yet completely automated. The catalogue describes the hand-cut process by which many early chip diagrams are made: “After the design was hand drawn on paper, operators had cut the circuit patterns into red cellophane-like sheets of rubylith. The design was then reduced photographically.” Details of chip diagrams are printed to emphasise their decorative nature. The publication goes to significant lengths to detail the visual legibility of the object of the microchip, and details neither the manufacturing process itself nor the workforce, placing all emphasis on the visual aspects of the diagrams and their analogues in MoMa’s collection. The blueprints in the exhibition were added to it.

The catalogue places the exhibition in the longer canon of MoMa’s expansive definition of design. It specifically refers to the 1934 show Machine Art, one of its first design shows. Philip Johnson, founding Chairman of MoMa’s Architecture Department, deemed this show to originate from an interest in the ‘aesthetic merit of certain industrially manufactured objects’. He goes on to specify that these objects are ‘created without artistic intention’. Machine Art’s accompanying publication is a catalogue in both the museological and the commercial sense, displaying vendors and prices for each item exhibited. Yet inarguably, with accession of industrial applications and household appliances alike into the museums collection, this exhibition is indebted to the art historical canon of the readymade.

Obviously referred to in the title, but not in the exhibition texts, is the canonical 1970 MoMa exhibition Information, one of the first international (here meaning: European and Northern American) survey shows of conceptual art which brought together a generation of artists engaged with politics and the media, such a Hannah Darboven, Adrian Piper, Vito Acconci, Hans Haacke, Ed Ruscha, Art & Language, and some one hundred others. Their work is described by the museum as challenging ‘institutional hierarchies’, using ‘ephemeral materials’, and thereby ‘evading typical museum classifications’, ultimately changing the way in which MoMa collects and presents work of art.

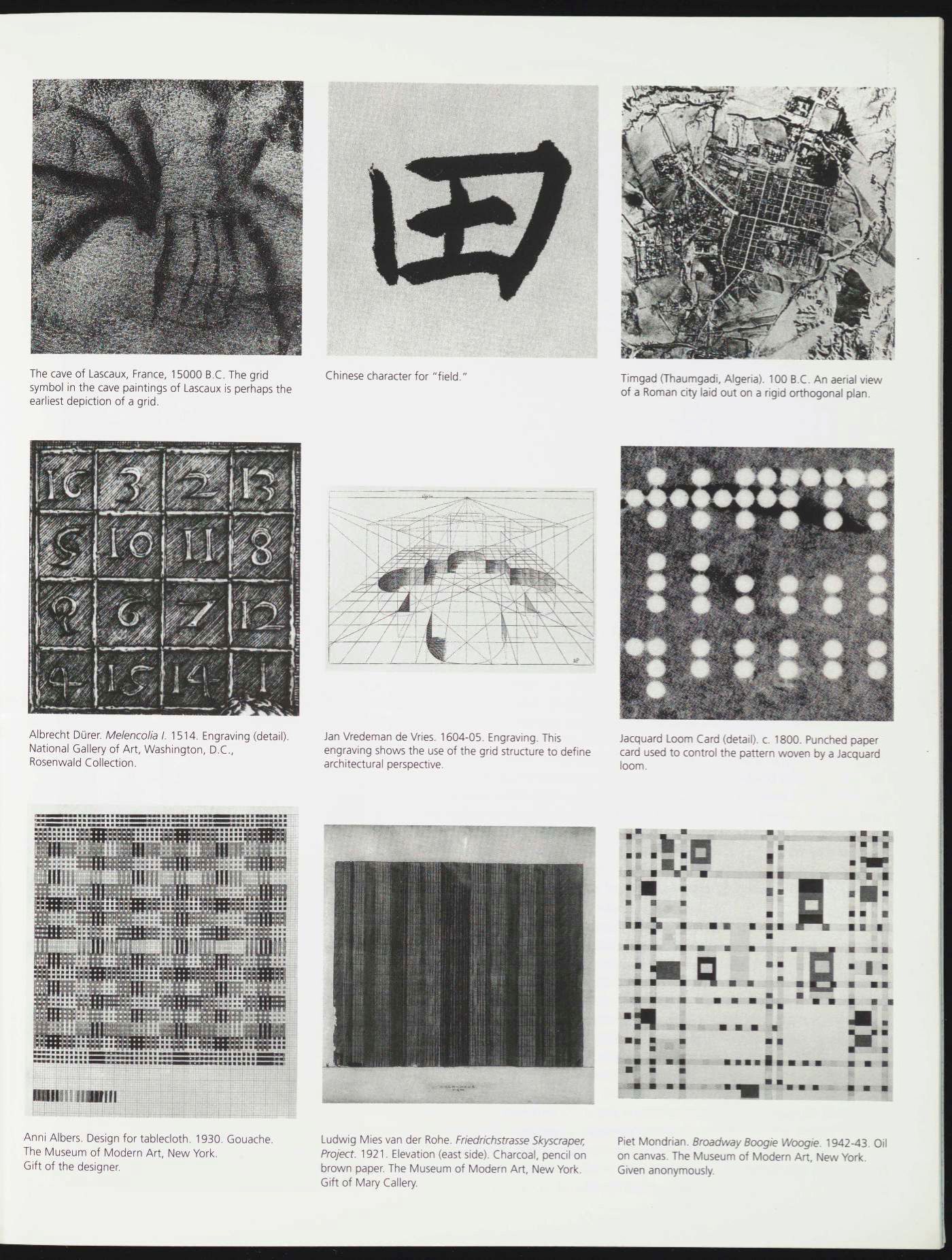

We have to read Information Art as an exhibition influenced by the impact of both pioneering shows. If the former influenced the possibility of drawings made for industrial application to be displayed at all, the latter affected the blurring formats of works that could enter into its collections. Cara McCarty is more indeterminate about the distinction between art and design than her predecessors, writing on Information Art that ‘technology does not have a form – we give it one’. This posits technology as the outcome of an almost inevitable development, whereby specific aesthetic decisions can be made by its designers. The catalogue contextualises the exhibition with a page that features nine works of art in the MoMA collection that find an analogue in the microchip diagrams, mostly focussed on the historical phenomenon of the grid: a cave painting in Lacaux; the Chinese symbol for ‘field’; a bird’s-eye view of a Roman city; an engraving by Albrecht Dürer; a Renaissance grid to demonstrate perspective; a Jacquard punch card (itself an artefact of computer history); a table cloth by Anni Albers; an early Ludwig Mies van der Rohe drawing; and the ultimate illustration of the grid in art, Piet Mondrian’s Broadway Boogie Woogie. So far, so square. But the process that is described in the text, that which makes this moment in microchip production so interesting, is one of handcraft; it finds a closer art historical analogue in Matisse’s cut-outs than in Mondrian.

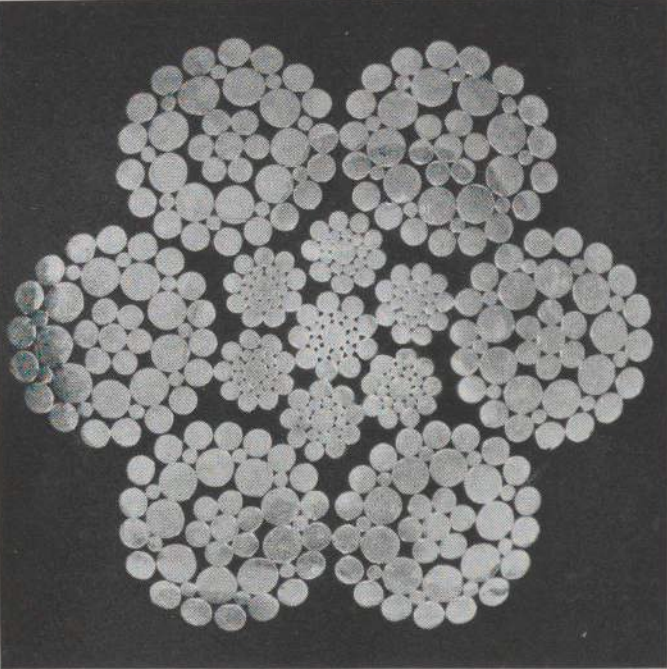

Is there a visual culture to components that elude our senses? Information Art emphasises the ‘mysteriousness’ of integrated circuits, a quality that evades the logic by which the diagrams are produced – whereby data is stored in uniform quadrants, and intricate circuitry can perform random access memory functions. Invoking the quality of mystery allows a museum visitor to appreciate the diagrams on the merit of their beauty, the beauty of Cartesian uniformity and variation. Perfect for a hominid pattern seeking brain. Microchips have ‘no visible moving components, gears, or levers, and they are silent’. In a sense, Information Art captured a moment in industrial design as it was leaving a scale perceptible to the naked eye. Thirty-five years on, it is unimaginable to repeat such an exhibition with contemporary microchip wafers. Automation of the manufacturing process has undercut any ties to craft – the scientists wielding scissors – that supports the presentation of microchips as a product of human ingenuity that is not aided substantially by the computerised processes of calculation. Yet MoMa’s attempt to integrate these circuits to the canonical history of art and design remains a hallmark attempt to explain the specific operations of items otherwise retreating into a black box of specific technological knowledge. The exhibition Information Art engages critically with the beauty of ubiquitously used objects, pinpointing this technological development not as an exceptional accomplishment but one in a longer history of human ingenuity.