Do Microchips have a visual culture? MoMa’s Information Art, 1990

February 18, 2025

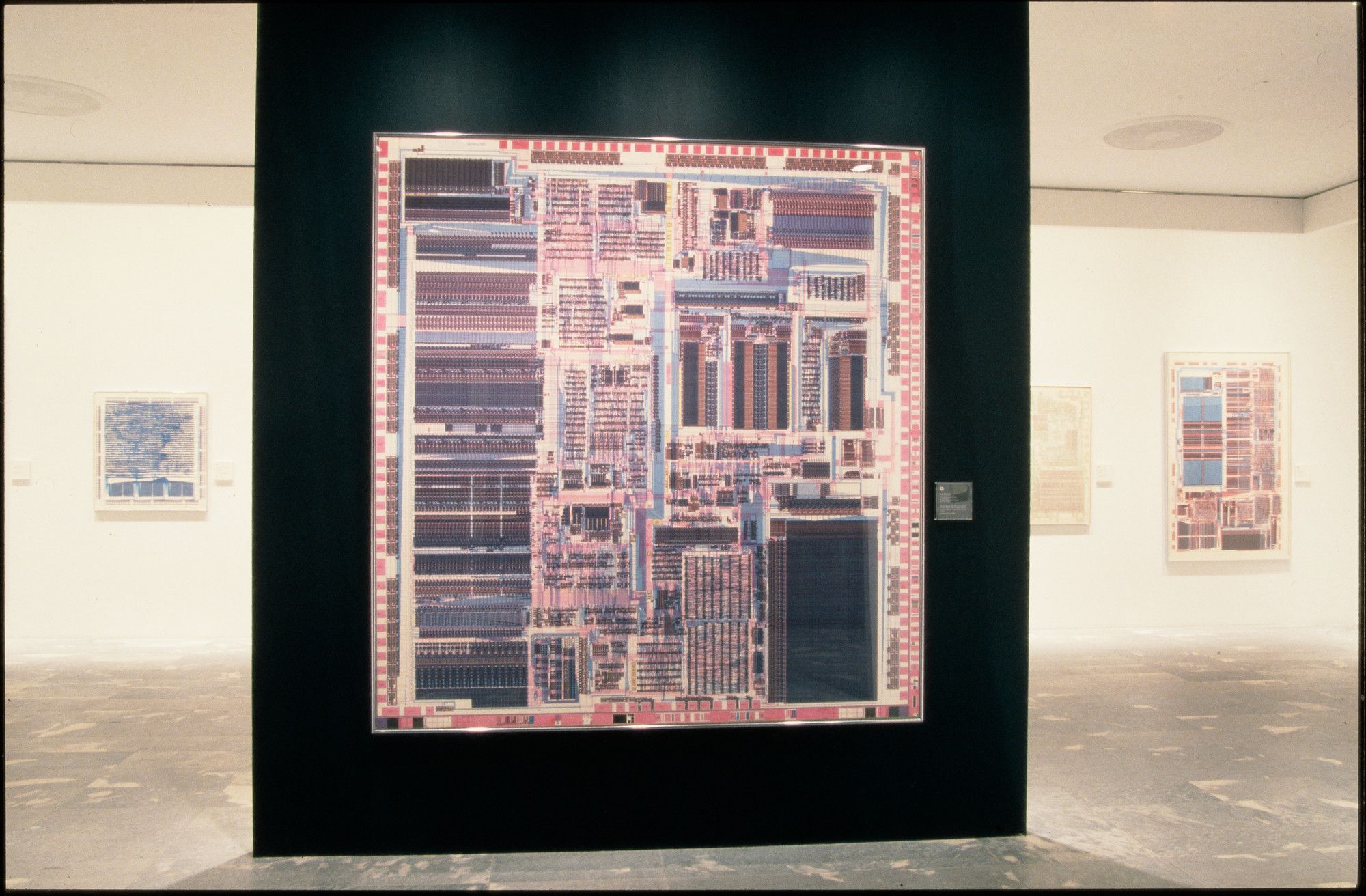

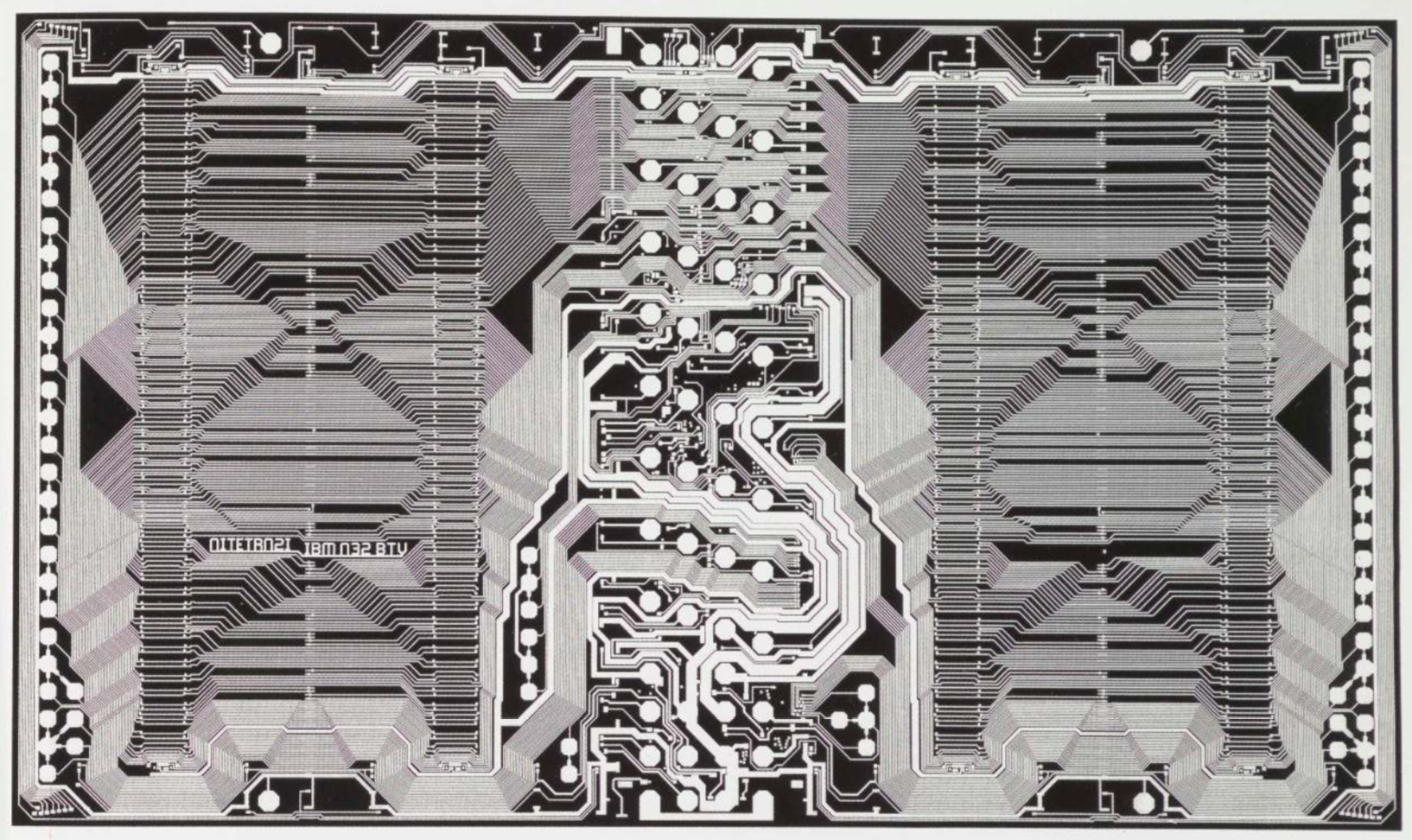

In 1990, a small exhibition at MoMA brought together a number of microchip diagrams. Curated by Cara McCarty, Information Art: Diagramming Microchips was made possible by the Intel Corporation Foundation, and featured 29 diagrams by the likes of Texas Instruments, IBM, Intel, AT&T Bell Laboratories, Hewlett-Packard, Xerox, and more. Carver Mead and Robert Noyce, both early inventors of the technology, were advisors on the show. Noyce, who co-founded Intel and Fairchild Semiconductors, was known as the ‘Mayor of Silicon Valley’. He the first to conclude that integrated circuits could be placed on a single, microscopic chip. He passed away before the exhibition opened; the catalogue is dedicated to him. The display at MoMA, by then, cements his legacy by presenting examples of his invention.

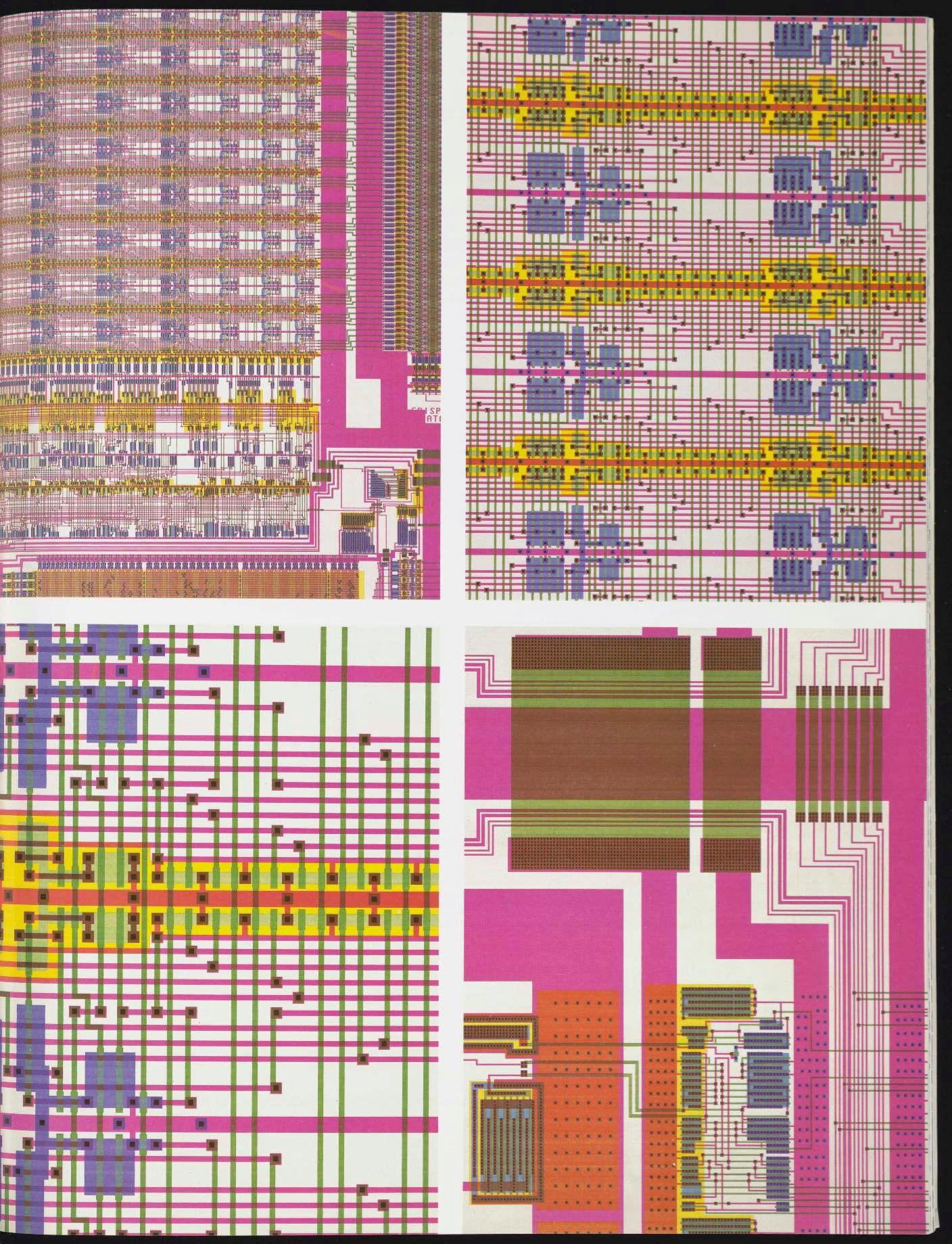

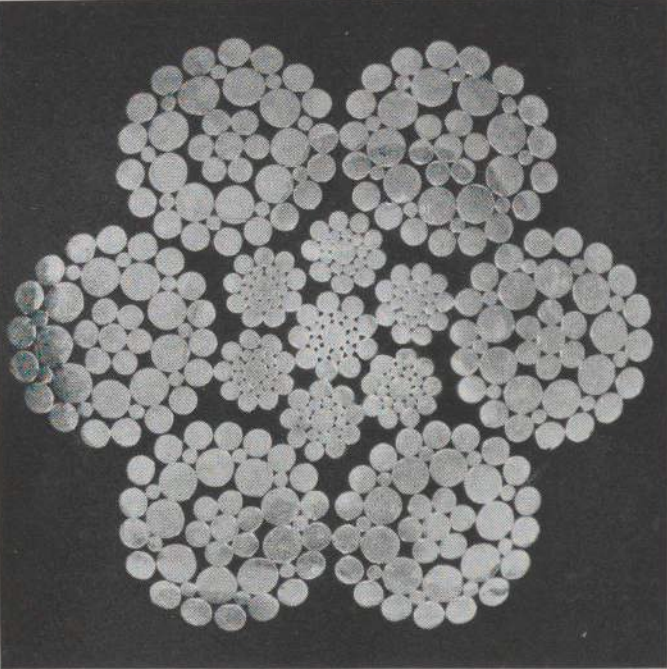

The catalogue is didactic, going to great lengths to explain the history and importance of microchips in layman’s terms. It emphasises craft elements in the production processes. Microchip diagrams are, still today, the templates from which microchips are produced. At the time of the exhibition in 1990, the design of these diagrams was the product of a manual process, one that had not yet been completely digitized, and their production had not yet been completely automated. The catalogue describes the hand-cut process by which many early chip diagrams are made: “After the design was hand drawn on paper, operators hand cut the circuit patterns into red cellophane-like sheets called rubylith. The design was then reduced photographically.” The visual legibility of the technology is key to how the diagrams are described. Readers will become acquainted with the difference between low-level and random-access memory, discern processing from logic units, and be able to dissect the top layers from a chip to where they are distributing power to at the lower levels.

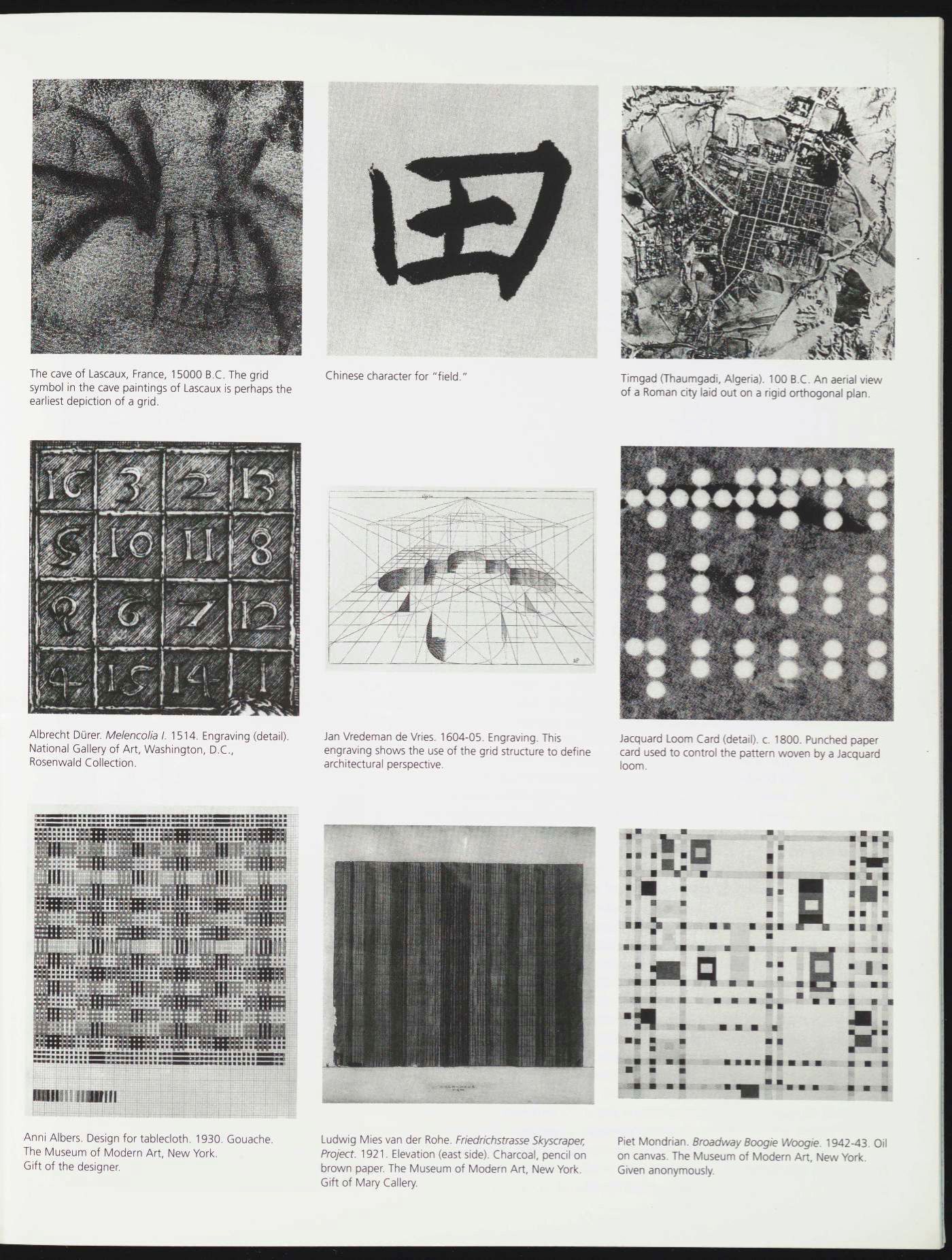

The diagrams on display were added to MoMa’s design collection. In the exhibition, they are presented as life-size prints on thin technical paper, emphasising their decorative nature to an audience familiar with the rationalism of the modernist canon. The catalogue contextualises this decision by featuring nine works of art in the MoMA collection that find visual resemblance the microchip diagrams. These predecessors to the chip are focussed mostly on the phenomenon of the grid in the art historical canon: a cave painting in Lacaux; the Chinese symbol for ‘field’; a bird’s-eye view of a Roman city; an engraving by Albrecht Dürer; a Renaissance grid to demonstrate perspective; a Jacquard punch card (itself an artefact of computer history); a table cloth by Anni Albers; an early Ludwig Mies van der Rohe drawing; and the ultimate illustration of the grid in art, Piet Mondrian’s Broadway Boogie Woogie. So far, so square. But the process that makes this moment in microchip production so interesting, is one of handcraft: microchip engineers would make the diagrams by “tracing the initial drawing of a component, photocopy it onto mylar” – a polyester film that provides high tensile strength – “then cut and glue it onto the diagram.” Ultimately, this production process is a collage technique, known even to the engineers themselves as the “paper-doll layout”. To reduce the chip to the sparse rationality of the visual grid speaks to an art historical canon that has centralised the Renaissance drawings of perspective at its apex. The microchip diagrams are reduced to a set of intricately decipherable visual functions, rather than a production process on the cusp of automation. That process was a product of its time, just like artists more contemporary to the diagrams itself, aldo collected by MoMa: Dadaists like Hannah Höch and Kurt Schwitters to speak to the radically different nature of collage as a generative technique; Man Ray, to address technologies of lens-less photography; and even contemporaries to the microchip diagram like Barbara Kruger and Robert Rauschenberg, whose work contextualises the technique in the artistic practices of the time. The production process of microchip diagrams finds a closer analogue in Matisse’s cut-outs than in Mondrian. The complexity of demonstrating the use of these objects to a general audience limits its art history to that of the canon of rationality, and places the technology of the microchip on a much broader timescale that spans prehistory until the 1950s.

The catalogue further situates the exhibition in the longer canon of MoMA’s expansive definition of design. It specifically refers to the 1934 show Machine Art, one of its first design shows. Philip Johnson, founding Chairman of MoMA’s Architecture Department, deemed this show to originate from an interest in the ‘aesthetic merit of certain industrially manufactured objects,’ which he specifies are ‘created without artistic intention’. The exhibition showed use objects as varied as cash registers, equipment for the shipping industry, springs, metallic ice cubes, and chemistry sets. Machine Art’s accompanying publication is a catalogue in both the museological and the commercial sense, displaying vendors and prices for each item exhibited. With the accession of industrial applications and household appliances alike into the museums collection, this 1934 exhibition was indebted to the art historical canon of the readymade.

Referred to in the 1992 exhibition’s title but not in the catalogue texts is the canonical 1970 MoMa exhibition Information, one of the first international (here meaning: European and Northern American) survey shows of conceptual art which brought together a generation of artists engaged with politics and the media, such a Hannah Darboven, Adrian Piper, Vito Acconci, Hans Haacke, Ed Ruscha, Art & Language, and some one hundred others. Their work is described by the museum as challenging ‘institutional hierarchies’, using ‘ephemeral materials’, and thereby ‘evading typical museum classifications’, ultimately changing the way in which MoMA collects and presents work of art.

Information Art can be read as an exhibition influenced by the impact of both pioneering shows. If Machine Art influenced the possibility of industrial applications to be displayed at all, Information affected the blurring formats of works that could enter into its collections. The curator of Information Art, Cara McCarty, is more indeterminate about the distinction between art and design than her predecessors, writing in the catalogue that ‘technology does not have a form – we give it one’. This posits technology as the outcome of an almost inevitable development, whereby designers’ interventions only encompass specific aesthetic decisions.

McCarty states that microchips have ‘no visible moving components, gears, or levers, and they are silent’. Information Art emphasises the ‘mysteriousness’ of integrated circuits, a quality that evades the logic by which the diagrams are produced – whereby data is stored in uniform quadrants, and intricate circuitry can perform random access memory functions. Invoking the quality of mystery allows a museum visitor to appreciate the diagrams on the merit of their beauty, the beauty of Cartesian uniformity and variation. Perfect fare for a hominid pattern seeking brain.

Is there a visual culture to technological components that cannot be seen with the naked eye? Information Art captured a moment in industrial design as it was leaving a scale perceptible to unaided human vision. Thirty-five years on, a contemporary exhibition of microchip manufacturing would have to grapple with its relative invisibility. Automation of the manufacturing process undercuts ties to craft – the scientists are no longer wielding scissors. Contemporary microchip manufacturing is aided substantially by computerised processes of calculation precise to the nanometre scale. MoMa’s attempt to integrate these circuits to the canonical history of art and design remains a hallmark attempt to make public the specific operations of items otherwise retreating into a black box. Information Art centred the production process of microchips as design, at a time when these components were becoming ever more ubiquitous, and its production microscopic, automated, and highly specialised. Information Art finds a critical beauty within these diagrams, emphasising the production of components that by now enable the display of so much other art. The presentation of those prints in the context of the museum remains a historical attempt at the demystification of microchip technology as a pinpoint in the entire range of human ingenuity.